|

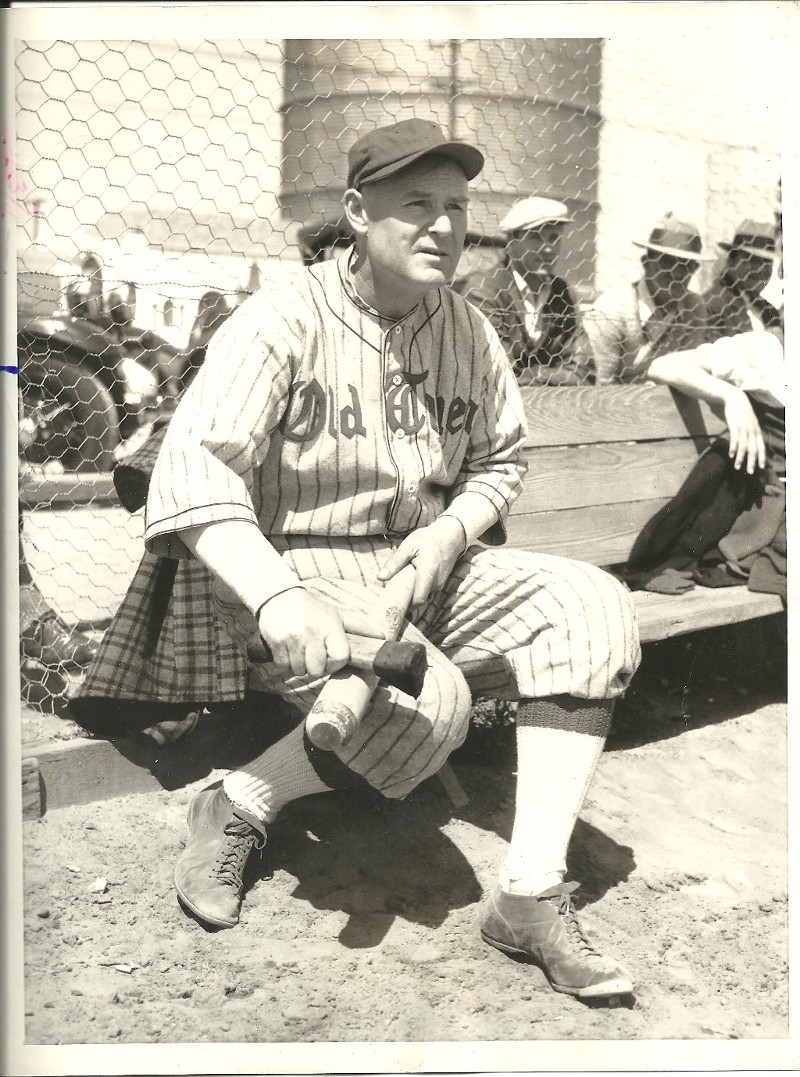

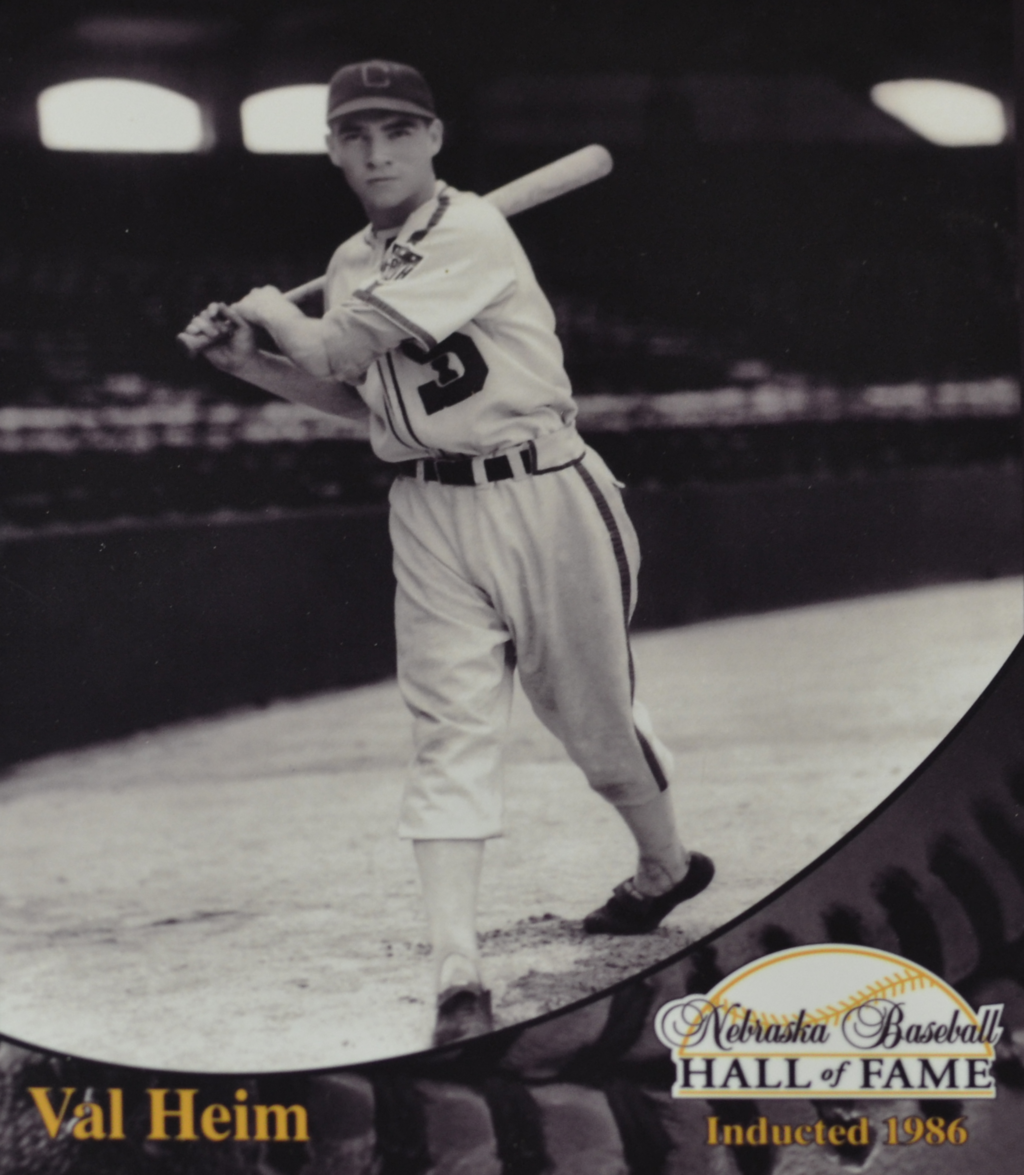

This article was written by Monty Nielsen. In a four-year voyage to an all-too brief career in big league baseball, Val Heim embarked in 1938 from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. He sailed on to Jackson, Mississippi, Jonesboro, Arkansas, and Waterloo, Iowa, before commencing his big-league career at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois, in late August 1942. His excursion began with an American Legion Post baseball entry in Channing, Michigan in 1938,1 when Heim was an upperclassman at Iron River Michigan High School. After graduating from high school in the spring of 1939, Heim expected to enroll in college that fall. However, his father, Raymond J. Heim, a conductor on the “Milwaukee Road” railroad, dissuaded him from that pursuit,2 leaving open other potential paths to explore. Instead of matriculating at college or seeking employment in the railroad industry, Heim chose to go south to a baseball school to search out and pursue his life’s ambition of playing big league baseball. Fast-forwarding 80 years to 2019, at age 99, Heim held the unique distinction of being MLB’s oldest living player before passing away on November 21, 2019.3 Ray and Cora Lueloff Heim were married on June 1, 1916, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Val Raymond Heim was born on November 4, 1920, in Plymouth, Wisconsin, the first of two sons, to Ray and Cora. His only sibling, Raymond Samuel Heim, was born on June 23, 1926, in Channing, Michigan.4 The family relocated frequently due to Ray’s job on the railroad, while school-aged Val participated in and excelled at competitive sports. During his high school years, in addition to varsity sports, Heim played baseball for a Channing Michigan Junior League squad. The team claimed an Upper Peninsula championship title.5 In 1939, an 18-year-old Val Heim enrolled in the Ray L. Doan Baseball School in Jackson, Mississippi.6 He studied under the experienced and knowledgeable Johnny Mostil, a former Chicago White Sox outfielder in the 1920s. “Mostil, who was running the school, along with Dizzy Dean and another former major leaguer Gabby Street signed him to a Sox contract”7 with the Jonesboro White Sox of the Northeast Arkansas League. Mostil became manager a year later. Heim quickly had risen to the top of his class, completing his first basic course of study in baseball before advancing to the minor leagues. Suddenly at 19-years-of-age, he was a professional baseball player. William J. “Billy” Webb, general manager of the parent Chicago White Sox, sent Heim a letter in March with a train ticket and instructions for spring training that included bringing “woolen shirts, jacket, shoes, glove and supporter.”8 But before departing the baseball diamond classrooms of Jackson for spring drills in Jonesboro, Heim was the starting centerfielder for Johnny Mostil’s Doan School White Sox squad versus Gabby Street’s rival Cardinals unit on Gabby Street Day, Sunday, March 10, 1940.9 Under new skipper Mostil, Jonesboro leapfrogged from last-place in 1939 to second-place in 1940 in the four-team league. Heim played in all but one game and walloped 41 extra base hits. The Jonesboro press wrote somewhat sardonically of his 1940 season performance. “His hitting was nothing to blow about…when he wound up with a .260 average.”10 However, at season’s end, the 5’ 11,” 175-pound outfielder ranked third in the NEAL with 27 doubles. Dissecting another of his tools, the Jonesboro sports reporters keenly observed, “It was a rifle arm that had the Chicago White Sox officials watching the then 19-year-old kid.”11 These same press box jurors further proclaimed, “Heim’s true aiming arm is probably the best ever seen in this league.”12 Heim threw right-handed but batted left-handed because he discerned it was two steps closer to first base. Heim’s sophomore season was split between Jonesboro and the Waterloo Iowa White Hawks of the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League. The totality of the 1941 season was Heim’s best during his professional baseball lifetime. Through 88 games at Jonesboro, Heim batted .323, with five home runs. He fielded .974, with 133 putouts. The Jonesboro team, however, was destined for a third-place finish in 1941, but neither outfielder Heim, nor manager Mostil would be wearing Jonesboro uniforms at season’s end — each was promoted to Waterloo. Prior to Heim’s late season promotion, he ranked at or near the top among NEAL leaders in largely every offensive category, most notably, runs scored, total bases, and triples. He also led all league outfielders in double-plays turned.13 The Jonesboro press classified Heim’s throwing arm as spectacular, which significantly enhanced his twin-killing prowess. Their assessment of his ball hawking skill was painted as masterful. “The way Heim laid back a couple of steps, then started running forward just a split second before the ball reached him in order to cut out two necessary steps in his throw was a beautiful thing to watch.”14 And to complicate matters further for the would-be sacrifice-fly beneficiary, “It was practically impossible to score from third when the ball was hit to Heim.”15 The now-20-year-old outfielder had made substantial progress at the plate and in the field in his less than two full seasons with the Jonesboro White Sox. So, the jump from Class D to B professional baseball was a smooth transition for Heim — his batting average in 35 games with the White Hawks was .328. He connected for 10 extra base hits, albeit with no home runs. His combined season Jonesboro-Waterloo batting average was .325, two points higher than his early exit average at Jonesboro, and his slugging percentage was a blended .439. The 1941 Waterloo team, however, finished in fifth place under new captain Mostil. Heim began the 1942 season back with Waterloo. He played in 112 games, compiling a .271 batting average, and hitting eight home runs. However, he registered a fielding percentage of .954, with 241 putouts, uncharacteristically committing 12 miscues. In late August, he signed his first major league contract with the Chicago White Sox. A newspaper article from Heim’s personal collection proudly noted that “Val Heim, former Iron River Michigan high school grid star and member of the Redleg baseball team four years ago, has joined the Chicago White Sox baseball team to bolster Manager James Dykes list of injured and enlisted men.”16 Heim, cruising through the lower minors, was now suddenly propelled to the parent club. Heim’s early career ambition was unfolding. In his inaugural major league contest on August 31, 1942, against Connie Mack’s Athletics at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, youngster Heim immediately made a good first impression, and it was not wasted on the press. “Youthful Val Heim…received his major league baptism playing left field for the Chicago White Sox and helping Manager Jimmy Dykes’ Pale Hose defeat the Athletics in the second game of a doubleheader … “Kid Heim,” as the Chicago papers have tabbed him, made an auspicious debut in a 5-0 win over Philadelphia. In his first turn at the plate in the big leagues, Heim sent a bouncing single over the head of pitcher Lum Harris and scored on an error. He roamed the outfield with the sureness of a veteran and made three putouts … Dykes, Sox manager, has stated that if Heim and Bill Mueller prove themselves, both rookies will be used as regulars in the outfield.”17 Two days later, against the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC, Heim had another single, his last safety until September 14, scored two runs, and drove in one in a 7-6 Chicago win. He also stole a base. The following afternoon in the second game of a doubleheader against the Senators, Heim was hitless, and lifted late for a pinch-hitter. Nevertheless, Val had flashed an earlier defensive gem that was noted by sportswriter Wayne K. Otto, “ … Heim went to the wall in deep right to make a catch as sensational as you see at any time … ”18 Following a 16-game road trip, the sub-.500 Pale Hose returned to Comiskey Park for a 12-game homestand — and the first opportunity for Sox fans to see Heim and Mueller. On September 12, Heim pinch-hit unsuccessfully in the nightcap of a doubleheader against manager Joe McCarthy’s Yankees. Yankees centerfielder, Joe Di Maggio, one of Heim’s two major league heroes19, batted fourth, going one-for-three, and scored two runs in the New Yorkers 7-1 win. The following day, in game two of a twin-feature with skipper Joe Cronin’s Boston Red Sox, Heim had two official at-bats, but no hits, against “Tex” Hughson. Boston won 5-0. The Beantown starting lineup included their superstar left fielder, the “Splendid Splinter,” Ted Williams, rookie Heim’s other major league hero20, en route to his first Triple Crown title in 1942. Until the finale of the series with Boston on September 14, Heim was struggling at the plate, and had not yet found his stride, starting two-for-19, batting a pedestrian .105. Despite his early hitting woes, Heim experienced the excitement of September baseball in a pennant race, even if it was the Red Sox and not the White Sox for whom this game was crucial. In this contest, Heim was reignited and emerged from his hitting doldrums; the rookie assumed a leading role in suppressing the Red Sox pennant pursuit in 1942. One local writer took note, “Collecting two hits in three trips for the Chicago White Sox Monday, Val Heim, formerly of Iron River Michigan, helped the Sox beat the Boston Red Sox, 4-0, at Chicago. The defeat put the Red Sox out of the pennant race. Heim, batting in third place, had two of the eight White Sox hits. His tally in the first inning after he had walked and scored on Luke Appling’s double, was enough to win the game.”21 The Sox resumed play at home two days later against the Philadelphia Athletics. Heim batted third between Wally Moses and clean-up hitter Appling. This trio of two-through-four in the lineup collectively rapped six hits, including a triple by Heim, his first major-league extra-base knock, and a one-bagger, while also scoring a run in the White Sox 4-2 loss to Mr. Mack’s A’s. Heim’s resurgence had resulted in four hits in seven trips to the plate in his last two games. On September 20, against the St. Louis Browns, in game one of a twin-bill at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, Heim contributed three runs in the Sox winning effort over the Browns, 6-5. He crossed home-plate for one run, and was credited with two RBI’s. In the nightcap, Heim’s encore included a double, his second major-league extra-base hit, as he chased in the Sox only two tallies in the top of the third inning. The Browns won 4-2. The next day featured game one of two against the Detroit Tigers at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. Heim delivered a single and another two RBI’s in the Sox 6-4 loss to Tommy Bridges and the Bengals. However, during the week just concluded, the 21-year-old Heim had hit at a .304 clip, with seven safeties in 23 at-bats, raising his batting average by over 100 points. He also drove in six runs — an encouraging sprint to the finish for the young fly-chaser. The last major league game in which Heim appeared was at Detroit, September 22. He played left field, batted second, and went 0-for-3. Dizzy Trout and the Tigers won, 9-2. The White Sox finished the 1942 season with a three-game sweep of the Indians in Cleveland. However, manager Dykes had re-inserted season starter and regular Myril Hoag in left field, replacing Heim. The veteran Hoag responded well and garnered seven hits in 12 at-bats versus the Tribe. Thus, rookie Heim had completed his 1942 season with a .200/.294/.267 slash line, drawing five walks and striking out three times in 51 plate appearances. Shining in the outfield, he had 23 putouts in 24 chances. After the 1942 baseball season ended, Heim voluntarily curtailed his major league pursuit, and served in the United States Navy Air Corps in World War II.22 He joined rather than leaving himself open to the Draft23 in 1942, and first “was stationed at Lambert Field in St. Louis, where he continued to play ball with the Naval Air Station Wings.24 From 1944 to 1945, he served on the island of Saipan, working with the Seabees to build roads and airstrips for bombers bound for Japan.”25 Heim honorably served his country, and while in the Navy received “the Asiatic-Pacific, American Defense, Victory and Good Conduct Ribbons.”26 Following Heim’s discharge from the United States Navy at the end of WWII, he returned to the Chicago White Sox organization to begin the 1946 campaign. Heim went to spring training in Pasadena, California. He split the 1946 baseball season with three teams. He began with the Triple-A Milwaukee Brewers 1-for-13 in eight games, but was reassigned to the Double-A Shreveport Sports .191 in 32 games. After his slow start, he was sent to the Waterloo White Hawks of the Class B Triple-I League. At Waterloo, Heim reunited with manager Mostil and resumed his pre-war productivity. He posted his best numbers with the White Hawks, averaging .317 with six home runs over 67 games. However, nearly four years removed from his big-league debut, Heim’s post-war return to professional baseball was defined by a downward trend, from AAA to AA to B-level. At the conclusion of the 1946 baseball season, the Chicago White Sox assigned Heim to the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association. The Sox appeared to remain committed to Val, as penned by vice-president Leslie O’Connor, who said of the assignment to Memphis, “We believe that this experience will greatly benefit you.”27 However, in December, the White Sox gave him a notice of transfer to Hollywood California of the Pacific Coast League. Unfortunately, Heim was to play for neither Memphis nor Hollywood. Heim joined the Hollywood Stars at spring training in 1947, but he soon contracted rheumatic fever and within a week he was hospitalized in California. Heim’s hospitalization was nearly six months in duration before he could leave and return home. During his hospital stay, Val received tremendous support from the parent White Sox organization, as well as the Hollywood Stars team, who paid the entirety of his $4,000 hospital bill.28 In addition, the press printed ways in which fans could send cards and notes of encouragement to aid and boost his morale. He eventually recovered and would resume playing professional baseball a year later. But there had been no 1947 baseball season for Val Heim.29 Showing great resilience, Heim returned to professional baseball in 1948 and played in 108 games for the unaffiliated West Palm Beach Indians in the Florida International League. Seemingly rejuvenated following a year’s absence from the game, he hit .297, with 27 doubles, eight triples, and eight home runs for the Indians. The dominant team in this circuit was the Havana Cubans, then a minor league affiliate of the Washington Senators. At age 27, Heim’s 1948 stint in the FIL was his last in professional baseball. He had played five seasons in the minor leagues, appearing in 570 games with over 2,100 plate appearances, compiling a .285 batting average, swatting 35 home runs, and amassing 883 total bases. Adding in his 1942 major league statistics, his five-year composite batting average was .284. In April 1997, Heim completed a 34-question survey constructed by the author, providing a personal perspective on his experience as both a player and manager for the Superior Nebraska Knights semi-pro baseball team. Val returned the survey with an accompanying letter, which summarized how he came to be a semi-pro baseball player, and where that led him: “ … The last year that I played professional baseball 1948 I married Betty Pfeifer30 in Florida … After that season I got a job in St. Louis … The job didn’t work out so in reading The Sporting News I came across an ad from Superior, Nebraska. They … were looking for baseball players to play semi-pro baseball in the Nebraska Independent League … I asked for a try out and reported to the manager of the Superior Knights … They held a spring camp of two weeks to look over ball players. If you were selected it was up to you to negotiate the terms that would be agreeable to you. In my case it was a job … provided by the Hill Oil Company, a home for our family that we had under contract to buy, a steer calf … and four months’ pay to play baseball with the Superior Knights. I was now a semi-pro baseball player free to move to the next higher bid … After the second year 1951 I had many contacts to play semipro baseball as well as offers to get back into professional baseball at the Triple A level. I decided to go to Albert Lea, Minnesota to play 1952 in … the Southern Minnesota League. Money was double from Superior, but the job wasn’t what we wanted. However, we did decide to go back to Albert Lea the next year 1953 for more money and a better job. Superior then made a counteroffer with more money, manage the Superior Knights team 1953, 1954 and a much better job at the Ideal Cement Plant. I finished my baseball playing in Superior 1955. At that time a semipro player that ended up with a good job was way ahead of a professional ball player … ”31 Many baseball personalities, including former major-leaguers Connie Creeden and Doyle Lade, as well as future major-leaguers Tom Hurd and Russ Snyder, toiled for the Superior Knights. Teams of prominence, such as the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs,32 enhanced the visitor’s dugout. A testament of one event that is part of the legacy of the Superior Knights was the presence of a future National League MVP, and later MLB Hall of Fame inductee, at tiny Memorial Stadium in Superior, Nebraska, in 1953. Heim recounted a conversation that he had in his first season as manager, about a potential player transaction: “I was looking for a shortstop and after a game with the Kansas City Monarchs I talked to their manager Buck O’Neil about my needs for a shortstop. Ernie Banks’ name was mentioned along with two other shortstops. The manager told me that Banks was ailing with either a sore arm or leg disability and that maybe Bill Holder, a good player, also, might be able to help us more at this time. We settled on Holder although he was not the caliber of Banks, he was not having any physical problems.”33 Bill Holder integrated the Superior Knights in 1953. Ernie Banks integrated the Chicago Cubs that same year.34 Were there other Black players of note who brought their skills and talents to the level of the semi-pro Nebraska Independent League in the early 1950s? Heim recalled that “McCook had two good Black players, Mickey Stubblefield and another named Horace Garner.”35 In an April 12,1997 letter, Val proclaimed, “Baseball has made the complete circle. The professional ball player of today is nothing more than a semi-pro player of my day, playing for the highest bidder in any town with any team. If you are good enough you can play any place you want.”36 Despite an abundance of many good players, the semi-pro Nebraska Independent League folded in mid-season 1955 due to severe financial issues, among others. Heim’s baseball life, too, had made a complete circle — his course completed, retiring from baseball in Superior, Nebraska. Fortunately, with some earlier foresight, Val had negotiated a good job, a house, and a modest start to a cattle herd, that gave him and his young family a means to seamlessly transition to life after baseball. Reflectively, Heim concluded, “Baseball has always been a great part of my life and it was a wonderful feeling when I put on a Chicago White Sox uniform and played my first game in the major leagues.”37 In a questionnaire from the American Baseball Bureau, stamped March 13, 1947, Heim was asked “to whom do you owe the most in your baseball career?“38 Val’s reply was John Mostil, his former manager. Val R. Heim was inducted twice into the Nebraska Baseball Hall of Fame in Beatrice, Nebraska. He was first inducted in 1981 to the Distinguished Service wing for significant nonplayer contributions to baseball in Nebraska. He was inducted again in 1986, this time as a player, the more prestigious distinction of the two.39 In addition, Heim is among a select group enshrined in the Museum of Nebraska Major League Baseball in St. Paul, Nebraska. This museum is for current and former major league baseball players with ties to Nebraska.40 Val Raymond Heim Sr. passed away on November 21, 2019, in Superior, Nebraska, at 99. He was interred at Evergreen Cemetery in Superior. Val and Betty Heim were married over 71 years — she survived him. A daughter, Diane Heim Boyd, a son, Val Raymond Heim Jr., several grandchildren and great grandchildren, plus countless family and friends also survived him. Acknowledgments This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson, Rory Costello, Alan Cohen, and Bruce Harris, and fact-checked by Paul Proia. Sources Baseball-almanac.com. Baseballdope.com. Baseball-reference.com. SABR.org. Hays, Hobe. Take Two and Hit to Right: Golden Days on the Semi-Pro Diamond. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. Clippings about minor league, military, and major league games, and interviews from mostly unidentified newspapers in Val Heim’s personal scrapbook, 1940-1946. Formal business letters, contracts, and personal correspondence from team officials in Val Heim’s personal scrapbook, 1940-1946. Thirty-four question survey constructed by the author, and completed by Val Heim, including a personal letter to the author from Heim, dated April 12, 1997. Personal conversations with Val R. Heim Sr., my friend; Val R. Heim Jr., my friend and high school classmate, who generously shared his dad’s personal scrapbook; and Ervin Nielsen, my dad. |